Tapping through my Spanish language app, I think how different it was for you, all those Christmases ago in the early sixties. We talked about it once in your first-floor kitchen as the steam condensed on the window in nonsense patterns I couldn’t read, mottling and screening the garden outside.

I’m coming home for Christmas and the language is English.

The signs are English, the eavesdrops are English, the announcements are English. Even the schadenfreude is more English than German as a blustery man with a fringe like a pointed leaf crashes into the train door a second too late; I smile, thinking the ooh dears and whoopses are as English as they come.

We speed out of London Bridge. I listen to my ‘journeys’ playlist, watching the familiar world pass by. It all feels like mine: comfy, almost snug. I observe the drenched streets, the cattle blurs and glistening fields; I watch the people reading the same bestsellers, having the same conversations, using the same phones; I wrap myself up against a frosty draft and watch the bare branches delineate winter on the steel sky.

As he turned his small brown head to shout at his attackers, you thought you glimpsed my father.

Tapping through my Spanish language app, I think how different it was for you, all those Christmases ago in the early sixties. We talked about it once in your first-floor kitchen as the steam condensed on the window in nonsense patterns I couldn’t read, mottling and screening the garden outside.

The story you told me was about the realities of living en el extranjero, about your own homecoming to Spain from an England that was still strange to you. It was a sombre story, forged on the necessity of strength. It presented England back to me as somewhere newly imagined and opaque as a stormy night.

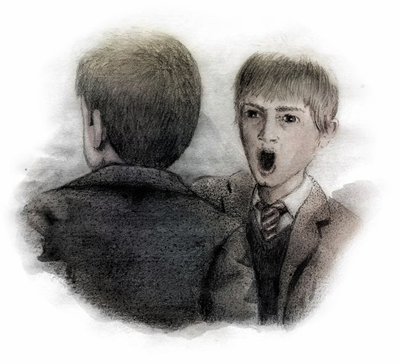

You remembered how, on the last day of term at Treydle School before the Christmas holidays, you saw home in a bullying of boys. They marched in pairs, playing at formality like little ones do, until one child was shoved out against the wall. As he turned his small brown head to shout at his attackers, you thought you glimpsed my father, your beloved Samuel—silvery-blue eyes glimmering like candle wax and a nose that was almost the reflection of yours—just like that final look when you left him with Abuela, his granny Pilar, a year before in that old house at the top of the hill in Coruña.

When you went back to the school kitchens to feed the pupils’ tiny mouths, donning your hairnet and dinner-lady apron, you thought of the rare treat of cooking for your own little boy. Empanadas and pulpo, orejas and lacón con grelos. You tried to remember the last time. Gloves on the table and Jesús was late. You think it was caldo gallego. Little Samuel wasn’t sure about the kale.

He was only four, and you’d promised his open, uncomprehending face that you would only be gone a short while. Back then, even six months away seemed impossible. But you couldn’t bear that endless, fruitless cycle you’d found yourself trapped in: trudging into town, following dead-end leads, returning jobless and sitting in the small room above the kitchen where the horizon out the window seemed to be closing in with the rain, strangling a little tighter every day.

So you went away and found jobs in an English school. And once there, it was difficult to come home, as much as you missed it and as much as you wanted to see my father. You had to fit in with the terms and, besides, it was expensive to travel. You waited, you put it off. Until, finally, at Christmas, you decided it was time to visit home.

Pilar had no phone so you were returning unheralded, travelling blind to a family left behind but not forgotten. You and Jesús talked about home that evening.

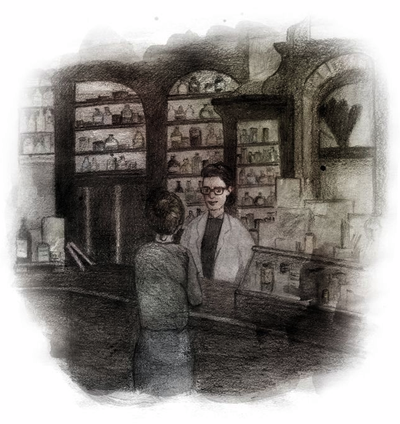

That time in the pharmacy when you couldn’t explain yourself and found instinctive pleasures of Spanish on your tongue.

You slept the night before the holidays like you were done with work forever. It felt like the end. You dreamed of all the strange, uncomfortable things and allowed them to drain from your bones: the useful expressions you’d got from phrasebooks and dictionaries, the language you’d absorbed over the year, conversations with the locals—rejection and awkward, tentative kindnesses—and the mocking jibes from some of the children at the school; that time in the pharmacy when you couldn’t explain yourself and found the instinctive pleasures of Spanish on your tongue. The pharmacist laughed.

‘I’m sorry, ma’am, I really… I don’t…’

She laughed because she was embarrassed, but for her this was only one interaction, one tongue-tied misunderstanding. For you, it felt like all conversations, an on-going experience that alternately numbed and riled you.

After four months, you started going to church on Sundays. Other than Robert Price, the mechanic, people didn’t go out of their way to make you feel welcome, but neither did they pay you any negative attention. You could come in and sit and sing along, mumble the prayers, follow the prompts in the service leaflets, kneel when everyone else was kneeling, stand when everyone else was standing. You had your first cup of English tea and it was perfect, soothing and mild, and even though it kept you awake, it quickly and happily became a part of your routine. All of this was English, but it was an Englishness that you felt you could slot in with inconspicuously: an Englishness that began to feel like yours.

You left at dawn, just as the rain stopped, and took an Argentinian boat. It carried you from Southampton to Coruña, and then went on to Vigo before crossing the Atlantic for South America.

A family reunion, a fiesta with everyone coming together.

You arrived in Coruña to a city glooming happily, boats bobbing thickly in an ashen water and the smell of the sea clinging to your clothes and your hair. All around, the Galician hills sprung vividly through the mist, verdant with promise. And there, that feeling of home: immediate, like the telegraph poles and hedgerows when I get off my train, you felt everything as yours, everything as Spanish, everything haunted by memories; and even the sad memories could feel comfortable, like a second skin. Your detached apprehension of a foreign land gave way to something fast, fluid, easy.

A short taxi ride in a rickety car with poor suspension and a smoky stench, and you’d reached Pilar’s street. You could see her house at the top of the hill, and just beyond the bend in the road, the flash of a red ball and a small boy playing.

Even from a distance, you knew it was him, you knew it was Samuel. You recognised the colours of him, his gait, the curve of his shoulders and the shape of his head. Jesús had been complaining of a headache, but he lit up at the sight of his son and took hold of both suitcases, telling you to go, go, go on ahead, because he saw you could hardly hold yourself back as it was.

He laughed as you ran and cried out: ‘Samuel, Samuel.’

Samuel heard his name in an unfamiliar voice. He stopped and turned, so much bigger now, so much more grown up; but still yours, a version of your dreams.

You can see him now, wearing zuecos—you tell me they’re clogs and wave a tea towel at the smoke that’s coming from the oven—and now he drops the red ball and it rolls into the gutter.

There’s something in his eyes.

You could see it before you were even ten metres away. Your own reflection: not home, not a mother, but a woman from across the sea, running towards him, shouting, not Spanish, not anything. There was no recognition in his little face; as far as he knew, you could have been an English woman.

You wiped a tear away as you told me how he screamed and fled, his silvery-blue eyes wide with panic.